The Defense Innovation Unit is bringing together the

best of commercially available artificial intelligence technology and

the Defense Department's vast cache of archived medical data to teach

computers how to identify cancers and other medical irregularities.

The result will be new tools medical professionals can use to more

accurately and more quickly identify medical issues in patients.

The new DIU project, called "Predictive Health," also involves the

Defense Health Agency, three private-sector businesses and the Joint

Artificial Intelligence Center.

The new capability directly supports the development of the JAIC's

warfighter health initiative, which is working with the Defense Health

Agency and the military services to field AI solutions that are aimed at

transforming military health care. The JAIC is also providing the

funding and adding technical expertise for the broader initiative.

"The JAIC's contributions to this initiative have engendered the

strategic development of required infrastructure to enable AI-augmented

radiographic and pathologic diagnostic capabilities," said Navy Capt.

(Dr.) Hassan Tetteh, the JAIC's Warfighter Health Mission Initiative

chief. "Given the military's unique, diverse, and rich data, this

initiative has the potential to compliment other significant military

medical advancements to include antisepsis, blood transfusions, and

vaccines."

A big part of the Predictive Health project will involve training AI

to look at de-identified DOD medical imagery to teach it to identify

cancers. The AI can then be used with augmented reality microscopes to

help medical professionals better identify cancer cells.

Nathanael Higgins, the support contractor managing the program for DIU, explained what the project will mean for the department.

"From a big-picture perspective, this is about integrating AI into

the DOD health care system," Higgins said. "There are four critical

areas we think this technology can impact. The first one is, it's going

to help drive down cost."

The earlier medical practitioners can catch a disease, Higgins said,

the easier it will be to anticipate outcomes and to provide less

invasive treatments. That means lower cost to the health care system

overall, and to the patient, he added.

Another big issue for DOD is maximizing personnel readiness, Higgins said.

"If you can cut down on the number of acute issues that come up that

prevent people from doing their job, you essentially help our

warfighting force," he explained.

Helping medical professionals do their jobs better is also a big part of the Predictive Health project, Higgins said.

"Medical professionals are already overworked," he said. "We're

essentially giving them an additional tool that will help them make

confident decisions — and know that they made the right decision — so

that we're not facing as many false negatives or false positives. And

ultimately we're able to identify these types of disease states earlier,

and that'll help the long-term prognosis."

In line with the department adding an additional line of effort

focused on taking care of people to the National Defense Strategy,

Higgins said using AI to identify medical conditions early will help to

optimize warfighter performance as well.

"Early diagnosis equals less acute injuries, which means less

invasive procedures, which means we have more guys and gals in our

frontline forces and less cost on the military health care system," he

said. "The ultimate value here is really saving lives as people are our

most valuable resource."

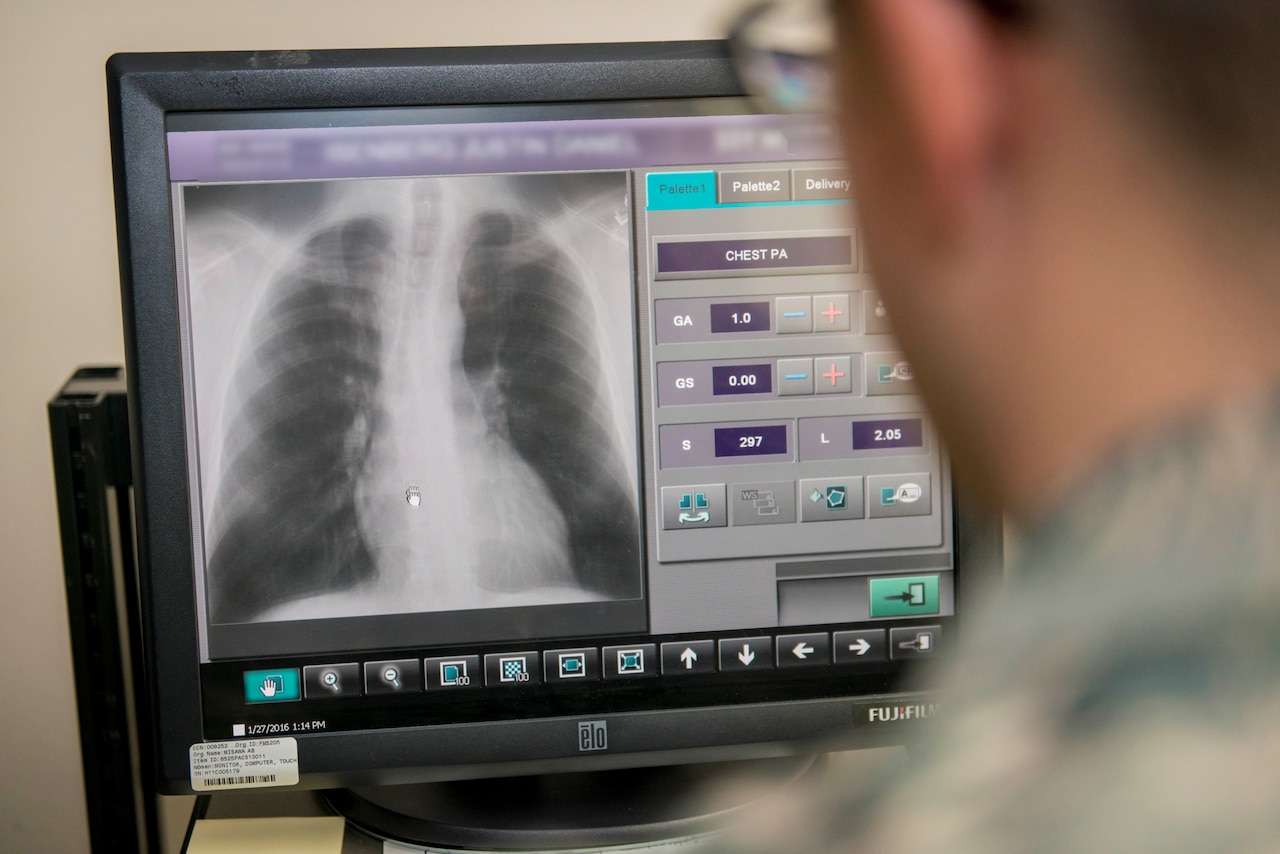

Using AI to look for cancer first requires researchers to teach AI

what cancer looks like. This requires having access to a large set of

training data. For the Predictive Health project, this will mean a lot

of medical imagery of the kind produced by CT scans, MRIs, X-rays and

slide imagery made from biopsies, and knowing ahead of time that the

imagery depicts the kind of illnesses, such as cancer, that researchers

hope to train the AI to identify.

DOD has access to a large set of this kind of data. Dr. Niels Olson,

the DIU chief medical officer and originator of the Predictive Health

project, said DOD also has a very diverse set of data, given its size

and the array of people for which the department's health care system is

responsible.

"If you think about it, the DOD, through retired and active duty

service, is probably one of the largest health care systems in the

world, at about 9 million people," Olson said. "The more data a tool has

available to it, the more effective it is. That's kind of what makes

DOD unique. We have a larger pool of information to draw from, so that

you can select more diverse cases."

"Unlike some of the other large systems, we have a pretty good

representation of the U.S. population," he said. "The military actually

has a nice smooth distribution of population in a lot of ways that other

regional systems don't have. And we have it at scale."

While DOD does have access to a large set of diverse medical imaging

data that can be used to train an AI, Olson said privacy will not be an

issue.

"We'll use de-identified information, imaging, from clinical

specimens," Olson said. "So this means actual CT images and actual MRI

images of people who have a disease, where you remove all of the

identifiers and then just use the diagnostic imaging and the actual

diagnosis that the pathologist or radiologist wrote down."

AI doesn't need to know who the medical imaging has come from — it

just needs to see a picture of cancer to learn what cancer is.

"All the computer sees is an image that is associated with some kind

of disease, condition or cancer," Olson said. "We are ensuring that we

mitigate all risk associated with [the Health Insurance Portability and

Accountability Act of 1996], personally identifiable information and

personal health information."

Using the DOD's access to training data and commercially available AI

technology, the DIU's Predictive Health project will need to train the

AI to identify cancers. Olson explained that teaching an AI to look at a

medical image and identify what is cancer is a process similar to that

of a parent teaching a child to correctly identify things they might see

during a walk through the neighborhood.

"The kid asks 'Mom, is that a tree?' And Mom says, 'No, that's a

dog,'" Olson explained. "The kids learn by getting it wrong. You make a

guess. We formally call that an inference, a guess is an inference. And

if the machine gets it wrong, we tell it that it got it wrong."

The AI can guess over and over again, learning each time about how it

got the answer wrong and why, until it eventually learns how to

correctly identify a cancer within the training set of data, Olson said,

though he said he doesn't want it to get too good.

Overtraining, Olson said, means the AI has essentially memorized the

training set of data and can get a perfect score on a test using that

data. An overtrained system is unprepared, however, to look at new

information, such as new medical images from actual patients, and find

what it's supposed to find.

"If I memorize it, then my test performance will be perfect, but when

I take it out in the real world, it would be very brittle," Olson said.

Once well trained, the AI can be used with an "augmented reality

microscope," or ARM, so pathologists can more quickly and accurately

identify diseases in medical imagery, Olson said.

"An augmented reality microscope has a little camera and a tiny

little projector, and the little camera sends information to a computer

and the computer sends different information back to the projector,"

Olson said. "The projector pushes information into something like a

heads-up display for a pilot, where information is projected in front of

the eyes."

With an ARM, medical professionals view tissue samples with

information provided by an AI overlaid over the top — information that

helps them more accurately identify cells that might be cancerous, for

instance.

While the AI that DIU hopes to train will eventually help medical

professionals do a better job of identifying cancers, it won't replace

their expertise. There must always be a medical professional making the

final call when it comes to treatment for patients, Higgins said.

"The prototype of this technology that we're adopting will not

replace the practitioner," he said. "It is an enabler — it is not a

cure-all. It is designed to enhance our people and their decision

making. If there's one thing that's true about DOD, it's that people are

our most important resource. We want to give them the best tools to

succeed at their job.

"AI is obviously the pinnacle of that type of tool in terms of what

it can do and how it can help people make decisions," he continued. "The

intent here is to arm them with an additional tool so that they make

confident decisions 100% of the time."

The Predictive Health project is expected to end within 24 months,

and the project might then make its way out to practitioners for further

testing.

The role of DIU is taking commercial technology, prototyping it

beyond a proof of concept, and building it into a scalable solution for

DOD.