Oct. 26, 2020

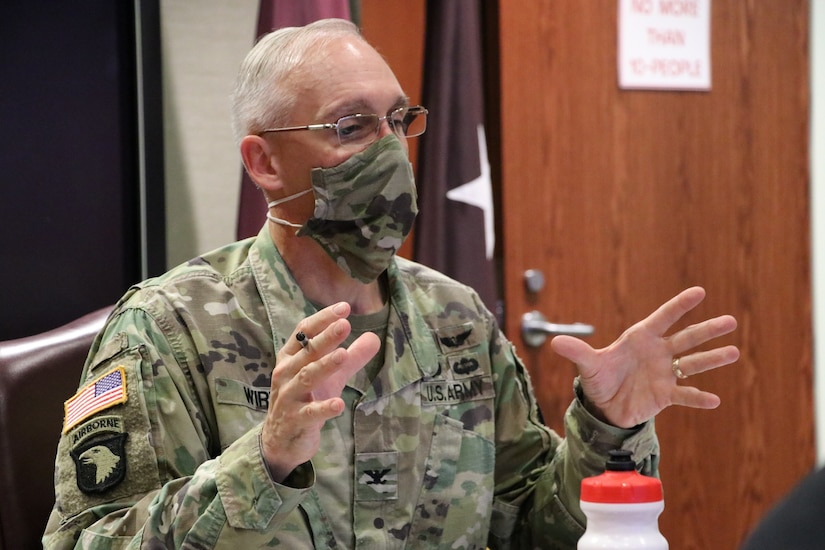

Dr. Mark Lewis, Director Of Defense Research And

Engineering For Modernization; Dr. Gillian Bussey, Director, Joint

Hypersonics Transition Office

Cmdr. Frey: All right. Okay. So we will close the

roll call for now. And if we have enough time at the end, I'll come back

to anybody who I didn't call. And we'll get started here in just a few

minutes with an opening statement from Dr. Lewis.

For those of you who haven't -- who I haven't talked to yet, my name

is Commander Josh Frey, I’m with OSC Public Affairs. I'll be

facilitating this call this afternoon. And thank you for joining us.

This afternoon, Dr. Mark Lewis, the Acting Deputy Undersecretary of

Defense for Research and Engineering, will provide a brief opening

statement on the Department of Defense hypersonics program and the

establishment of the University Consortium for Applied Hypersonics.

He will then be joined by Dr. Gillian Bussey, the Director of the

Joint Hypersonics Transition Office, for an overview of the consortium.

And then we will go into a brief question and answer session.

We'll have about 30 minutes for this event today. And this is on the

record and for attribution. If you have any follow-on questions or I

don't get to you by the end of the questions, then follow up with me and

we can try to have your question answered at a later time.

And with that, Dr. Lewis will now provide an opening statement.

DR. MARK LEWIS: Great, well, hey, let me start off by thanking

everyone for joining us. Really appreciate your time this afternoon. We

called you all together to make an announcement of a program that we're

really quite excited about. I hope -- I hope you will be as well. So --

if I -- if I can provide the context, I've heard a lot of familiar names

on the line so I know many of you have reported on our work in the past

on -- on high-speed flight, but to kind of set where we are, I think

all -- all of you know that one of our very top modern day priorities at

the Department of Defense is hypersonics. And our goals are pretty

straight forward. We want to deliver high-speed weapons at scale, and by

at scale we mean large numbers, into the hands of our warfighters, and

we also, by the way, want to develop defenses against weapons that some

of our peer competitors are in the process of developing or deploying as

well. So it's both offense and defense. And to this, we've

significantly accelerated research and testings. We have a number of

prototype efforts underway in the Department. And all these have the

goal of rapidly transition to programs of record, again, to get

high-speed weapons in the hands of our warfighters. So as part of doing

this, we developed a detailed road map. And that road map was -- was

developed in concert with the services and the various agencies,

including DARPA, Missile Defense Agency, Space Development Agency, but

we've taken a truly whole Department approach. And this approach isn't

just focused on research and development, but also on such issues as

supply chain and workforce and including education as you're going to

hear today. So an important element of this has been pushed for the

creation of what we call the Joint Hypersonics Transition Office, the

JHTO, and that's within the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for

Research and Engineering. As -- was mentioned, I'm currently the Acting

Deputy Undersecretary in that office. We've done that with tremendous

support from friends in Congress, those who recognize the importance of

investments in this area. So today, it's my pleasure to help announce an

important milestone coming out of the JHTO, the Joint Hypersonics

Transition Office. That is the formal kickoff of the University

Consortium for Applied Hypersonics. It's going to be led by Texas

A&M under the guidance of Dr. Rodney Bowersox in the College of

Engineering. And – and Dr. Bowersox and his colleagues have assembled a

multi-university team that will truly be our partners in exploring

hypersonics.

So -- without further adieu, I want to introduce the head of our

Joint Hypersonics Transition Office, Dr. Gillian Bussey. She's been the

person who led the effort to create, to define, and will ultimately be

the person to help guide and partner with this team of universities

under the consortium.

So, Gillian, turning it over to you.

DIRECTOR GILLIAN BUSSEY: All right. Thank you, Dr. Lewis. It's been a

pleasure working with you and the R&E Hypersonics Team getting this

consortium off the ground.

So establishing the University Consortium for Applied Hypersonics has

been my top priority since being appointed director of the JHTO in

April. When Congress provided funding and direction to establish this

consortium, they highlighted the important role that our country's

academic institutions play in national security-related technology

development. While we've always turned to our colleges and universities

to advance important technologies, this consortium is unique in its

diversity and scope. So hypersonics in particular requires integrating

advanced technologies from across a wide variety of disciplines. So this

consortium will bring together under one umbrella universities from

across the country. I think we've -- we've heard from almost every state

as a part of this initiative expressing an interest in joining. So

we'll bring in universities from across the country and researchers with

expertise, ranging from aerospace, chemistry, thermodynamics,

materials, artificial intelligence, possibly quantum, and more. So our

job is really to leverage this broadly scoped consortium to break down

the functional stovepipes and good ideas from research to operationally

useful capabilities and then perhaps most importantly, develop the

hypersonics workforce we need. You'll note that this is a consortium for

applied hypersonics. The Department is funding a good amount of basic

research in hypersonics, but we're finding that that's leading to some

of the more applied areas are not quite as healthy and not bringing

fresh blood into our workforce, into our industry. So this consortium is

going to -- is really based on something kind of new. We're focusing on

budget areas 6-2, 6-3, so more applied areas, and having universities

work on more sensitive technologies. That could include ITAR,

classified, things that are a little bit more closely connected to our

programs, to really help transition that workforce and to get students

and professors kind of working in more applied areas, working more

multidisciplinary and really treating them as a member of our team. So

this effort is consistent with the JHTO's larger purpose, which is to

synchronize and align the wide variety of cross-disciplinary research,

technology, transition development, and test efforts needed to

successfully produce hypersonic systems. We need to coordinate and align

to meet the warfighters' needs, to avoid redundancy, to focus our

resources on the most important and most promising technology

development areas. We work closely with Mike White, the Principal

Director for Hypersonics, on our activities, particularly our

hypersonics S&T roadmap, and the consortium activities that derive

from it, along with the larger view of the hypersonic vision. While I've

largely been speaking to technology development, an equally important

purpose of my office and the university consortium is to better

development the workforce. The symmetry of purpose between the JHTO and

the consortium in research and workforce development will carry us far,

and we couldn't have a better partner in this effort than the Texas

A&M Engineering Experiment Station. When we solicited whitepapers

from universities, non-profits, and small businesses to establish and

oversee this consortium, we received many high-quality responses. Two

stood out in particular with their expertise in running consortiums,

they're broadly inclusive in cross-cutting government structures

(inaudible), and a wide range of supports that they will provide to the

consortium and its members, is really quite amazing. They also presented

a plan to maximize opportunities for effective engagement between a

government and academic community beyond research projects. I will say

by choosing Texas A&M, I didn't -- I felt like we weren't choosing

just -- we weren't choosing a contractor. We ended up getting a partner

and a valuable member of our team. They really presented a great

proposal that shows that they really understand what the hypersonic

community needs and how the university systems can, you know, affect

that. The governance board that they empaneled includes many of the top

minds in hypersonic related research from across multiple universities.

Their plan includes integration of industry in an advisory capacity,

which is essential to ensuring how we can best transition technologies

to operational capabilities, and develop our workforce; tease outreach

efforts, which have garnered in over 500 faculty members from, I think

the number's up to 45 now, different universities so far, ensuring that

we have not only the diversity we need, but that we will hit the ground

running. Our intent is to release an initial tranche of 26 project

solicitations through the consortium to its members next month, and we

expect to award 20 million in funding to those proposals that best meet

our needs and will connect an initial virtual industry day associated

with that call. To wrap up, today is an exciting day for the hypersonic

enterprise and our partnership with Texas A&M will be of great

benefit to the nation. At this time, I'd be happy to take any questions

you might have.

DR. LEWIS: Thanks a lot, Gillian.

Cmdr. Frey: Okay. Now we'll go over to Steve Tremble from Aviation Week.

DR. LEWIS: Hey, Steve, how you doing?

Q: Great. Great, great to hear from you again. So I know it's

difficult to elaborate in this subject area, but can -- can you go into

any depth on an example or two of a -- of a problem that you think you

can solve or -- or at least address by going through this structure of a

consortium versus the other way DOD would handle basic research with

the universities?

DR. LEWIS: Well, actually, Steve, if I can jump in-- so, you

know--there's no -- when you say other way, I mean, we have many, many

different paths to work with the universities, everything from the

single investigated grants to the MURIs -- What are you looking to

contrast against?

Q: I mean, this consortium approach with sort of a central manager at

Texas A&M with the JHTO. That sort of coordinated process and --

and given things like aerothermal chemistry and all these other very

complex, interactive issues with hypersonics.

DR. LEWIS: So -- Gillian, let me take -- if it's okay, let me try to

jump in on that one and then feel free to chime in as well. So, let me

-- start by saying, look, Steve, I spent most of my own career as a

faculty member doing research in hypersonics. And the one thing I can

tell you is hypersonics is perhaps the most interdisciplinary subfield

that I know in aerospace engineering. A good hypersonic vehicle is a

fully integrated system. The engines and the airframes are more closely

coupled, more closely integrated than almost any other aerospace system

that I can think of. And so this is a -- this is an area that just is

crying out for multidisciplinary investigations. And that's what a

consortium like this allows us to do, all right? Instead of funding a

fluid dynamicist who's been working boundary layer transitions, and a

material scientist who's done work on (inaudible) materials, this

consortium allows us to get teams of faculty members together, in some

cases large teams, tackling these really complex, major problems. And

that's the beauty of this. Gillian, do you want to -- do you want to

fill in? You want to elaborate?

DR. BUSSEY: Yeah, so -- I think one thing I've noticed overseas, in

China, I've seen some of the research papers and they -- you look at

kind of the research papers coming out of some of these schools and it's

like you -- as a student, you could be exposed to every aspect of a

hypersonic vehicle design and we've seen from some of the press

reporting that some of these universities are actually designing and

flying vehicles. And so I -- have to think that that's done amazing

things to their workforce and might be part of the reason why that

they've had a lot of success with their programs and we're hearing about

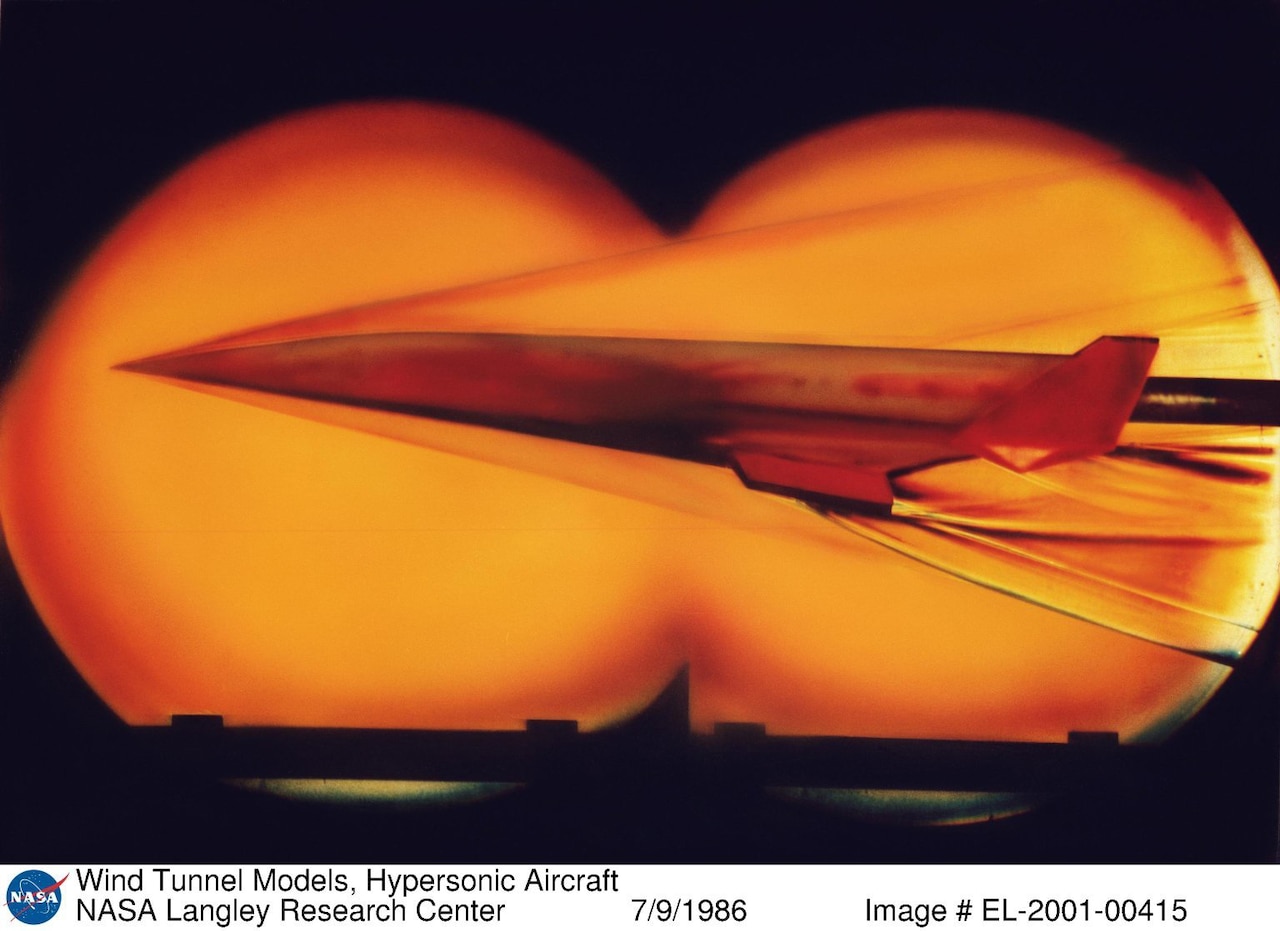

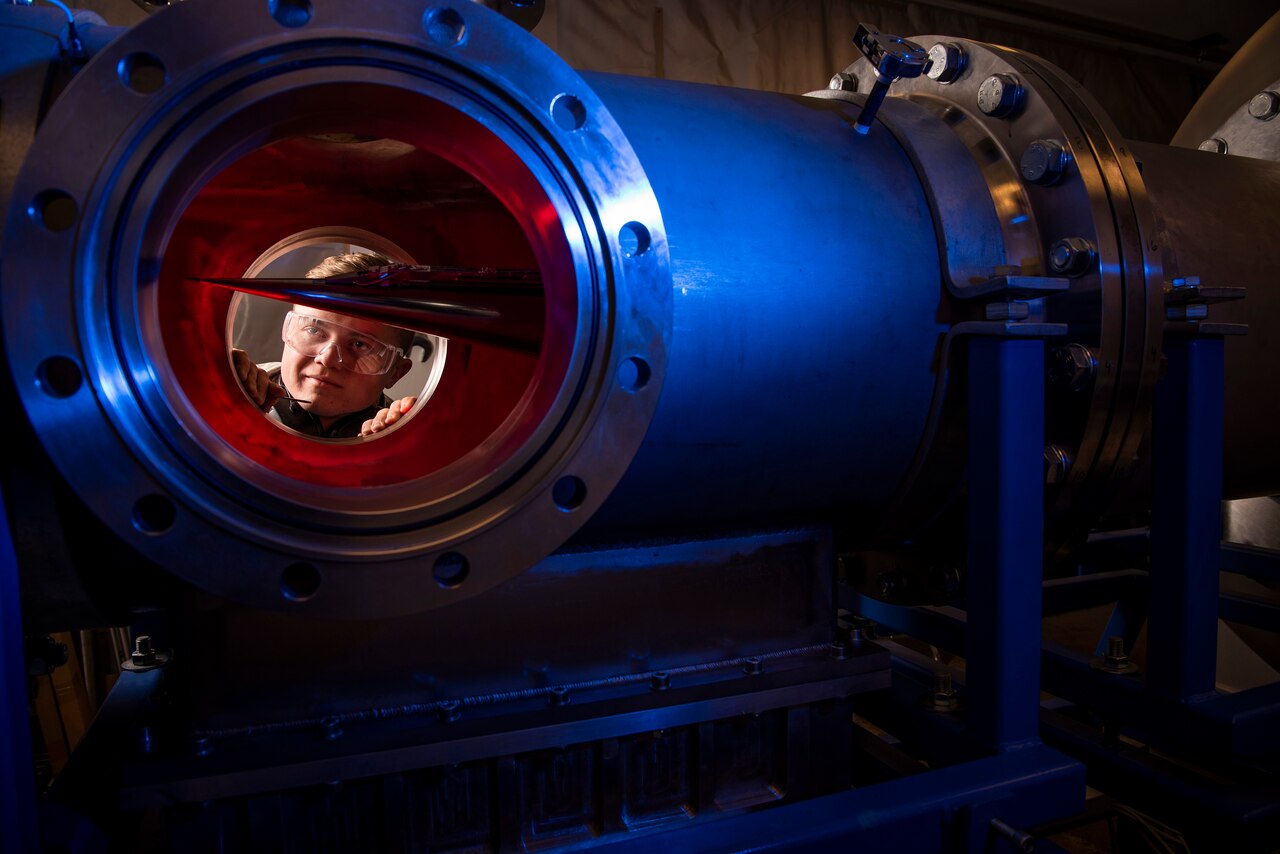

it in the press. So I think, like, for example, one paper I saw, they

had a university team was designing a vehicle and they were taking into

consideration rate of cross-section and survivability, as well as

aerothermal dynamics. They would then take that vehicle into the wind

tunnel and verify the performance. I could imagine a project like that.

You might also have another university working on the sensors that go --

new types of sensors that go into the wind tunnel to help characterize

the important elements of the flow that you need to know about. One

thing that we're doing with our consortium is we're trying to replicate

projects, multidisciplinary projects like that and -- that are more

applied. Ultimately, the gold standard would be to have this team

develop a vehicle and fly it. That really depends on our -- our budget

and kind of how things go, but for at least in your term, we plan on

having these things we call challenge projects. There'll be a couple of

them. They're multidisciplinary. They require teaming across

universities. They're similar to the MURIs that are in the 6-1 world

that -- folks like ONR and NASA and (inaudible) funds. I guess kind of

one idea might be, like, let's say you have a scram-jet engine and you

are trying to figure out how to provide better active engine control.

And so there's things going on with the inlet that affect that, there's

algorithms that need to be developed, there's sensors that need to be

developed, you've put in the wind tunnels to understand what's going on.

You're bringing in people who -- engine experts, you're bringing in

aerodynamics people, you're bringing in someone to develop algorithms,

you're bringing in G&C folks, you're bringing in the (inaudible).

It's a big team of people all working together and then students, when

they're part of these projects, when they graduate, they've had

experience beyond just their small -- beyond just their discipline,

they've actually had to do systems engineering and think about problems

within their area.

DR. LEWIS: Yeah. And Steve, I guess I -- let me emphasize to your

point that Gillian already made, but to really emphasize this, that as

part of this consortium, the university's going to be directly partnered

with us. They're going to be working on our actual real-world problems.

So they're going to be fully integrated in some of the things that we

do in this department. That's really kind of exciting. We already had

some universities that are kind of on our critical path, but this will

expand that relationship.

Q: That's great. Thank you.

Cmdr. Frey: Okay. And now we'll go to Kara Carlson with the Austin American-Statesman.

Q: Hi. So Texas as a whole, including Austin, has become kind of a

hub for both public and private defense tech research. And I was just

hoping to get some more information on how Texas A&M and just the

state university system as a whole might fit into the DOD's future

priorities and a road map as far as their own development of defense

technology.

DR. LEWIS: Oh, I love that question, because our universities across

the country are integral to the things that we're doing in modernization

priorities. So if I can step back, we've got a portfolio of technology

priority areas, including hypersonics, but also including such things as

artificial intelligence and microelectronics and directed energy. And

we're investing heavily across the department, but a large part of that

is the investment that -- and starting at the university level. And when

we looked to states such as Texas, we see incredible support. They

understand the importance of these technology areas for our warfighters,

for the Department, -- and frankly, they've risen to the challenge. In

Texas, University of Texas Austin, I look at their engineering program

and they've done some -- they've grown tremendously. They've built some

incredible capabilities that touch directly on our modernization

priorities, especially artificial intelligence and autonomy. Texas

A&M is also doing some really, really incredibly impressive research

across our list of priorities, not just in hypersonics. My close friend

and colleague, Dr. James Hubbard, is a faculty member at Texas A&M.

He has been doing some incredible work on autonomy, looking at the

future of unmanned aerial systems, is just one example. Other

investments being made across the board, again, addressing our

priorities. So I will tell you that we also -- when we looked at Texas,

we see -- I think a special appreciation for the importance of research

that is dedicated to the defense of our nation. And we in the Department

truly appreciate that.

Q: Okay, thank you.

Cmdr. Frey: Okay, Brittany Britto with Houston Chronicle.

Q: Thanks so much. I think my question kind of piggybacks on the

first question asked. When you're talking about developing weapons and

vehicles and doing real-world research, for our readers who might not

know much about hypersonic technology, are there any other kind of

relatable, I guess technology or inventions or projects that you're

looking to focus on within the next five years?

DR. LEWIS: So, you mean within -- you mean out beyond hypersonics or

within hypersonics? Can you -- I want to make sure I understand the

question.

Q: Yeah, within hypersonics, but if there's -- you mentioned it's, like, multidisciplined.

DR. LEWIS: Of course.

Q: I guess it doesn't relate to hypersonics, then just anything that you're focusing on and the initiatives.

DR. LEWIS: Sure. So -- let me -- I guess, let me take a step back.

So, as you probably know, hypersonic flight refers to flight in excess

of about five times the speed of sound. And there's a set of special

challenges in designing a vehicle that can travel at those speeds. We

look at hypersonics as being an enabling ability. It's not just one

thing. It's a range of systems. It's everything from cruise missiles to

longer range weapons, to basically high-speed airplanes, and maybe even

high-speed spacecraft, all right? The special challenges have to do with

when you're traveling at those sorts of speeds, it's difficult to

propel the craft through the atmosphere. But then you also have to deal

with the intense environment and incredible speed that is generated in

association with flight at those speeds. So, we've got a -- we've got a

whole range of subcategories and Dr. Bussey can go into more detail, but

everything from propulsion systems, what are the engines that we use,

to the high temperature materials that can handle the incredible heat

loads that you experience from traveling at those speeds. Also, the

special aerodynamics. So how do -- how do you shape a vehicle that

operates most efficiently at those sorts of speeds? So all those kind of

come together, and then the ability to control the vehicle. How do you

make sure it points in the direction you want it to point in? How do you

maneuver? How do you pitch? How do you yaw? How do you control it? How

do you build sensors that can operate in those sorts of environments?

But a long list of challenges that we've identified that this consortium

will be able to participate in. So, Gillian, did I miss anything on

that list?

DR. BUSSEY: No, but we do have a formal list that we've prioritized.

So we have six overarching technology areas that are priority. Materials

and manufacturing; guidance, navigation, and control; propulsion,

primarily air breathing propulsion; environments; phenomenologies, which

kind of refers to what is the vehicle experiencing, the

high-temperature gas dynamic around the vehicle, and the vehicle in the

atmosphere, your weather effects; applied aerodynamics and system

engineering, and then the sixth area is lethality and energetics. So I

don't believe you mentioned warheads. So that's -- we're looking at

issues related to warheads, blast effects, in that sixth area. But

pretty much every aspect of the hypersonic vehicle, we're going to be

looking at it, but from a more applied nature.

Q: Thank you.

Cmdr. Frey: Great. Thank you. Patrick Tucker with Defense One.

Q: Sorry, can you hear me?

Cmdr. Frey: Yeah, we can hear you.

Q: Okay, thanks. So it might be a little bit redundant, but if not,

(inaudible). The 26 project solicitations, can you tell us some of the

first ones or some of the biggest ones that are coming up next month?

Some more about them?

DR. BUSSEY: So we're still formulating them. And we're actually

trying to keep them a little bit close hold because this is going to be a

competitive solicitation, so we don't want to give anyone an unfair

head start. But they're focused in the six areas and they're generally

going to be -- we generally hope to have more projects in the first

three areas I mentioned as opposed to the last three because they are

prioritized. But you'll see a healthy spread across the different

disciplines.

Q: Okay. And earlier you mentioned that there are schools in China

where you have these multidisciplinary teams that are actually beginning

to, like, build aircraft. I mean, the Defense Department already has

formal hypersonics programs to build platforms. Is a (inaudible) fielded

craft. Is that an objective or will you be (inaudible) by way of

testing the hypersonics research environment that exists in China versus

the United States?

DR. BUSSEY: So it was brought up as an example, kind of the

environment they have. I think it would be our goal. Again, this is

funding dependent and depending on how things are going with the

consortium to have a flight test vehicle. I think some of you might be

familiar with the AFOSR-led BOLT program, which essentially is -- was

ATL and it's led actually by Texas A&M. And it's brought together

several in the hypersonics community working on a particular problem.

And they're flight testing a vehicle and they're going to get the

results and they're going to compare against their data. That's done

wonders for invigorating the workforce and it seems excited. They're

giving people relevant experience when they're in college beyond just

the lab and their classes. So it is my hope that we can replicate

something like that, but have it be more multi-disciplinary and a more

applied area, but we're just not there yet.

DR. LEWIS: If I can jump in, I do want to tell you, I'm often asked,

-- it's the story has been well-told about how much the Chinese have

imitated us, how they've duplicated some of our work, they've read all

of our papers, they've followed all of our research, in some cases

they've just stolen things hook, line, and sinker. And I'm often asked,

well, gee, should we be learning lessons from the Chinese? Yeah, we can

take the best of their ideas as well, and so I'm kind of -- I'm pleased

in this case that we've looked -- in this case, it's something that

they've done, and we said, yeah, we can do that, and in fact, we can do

it better.

Q: Thanks.

Cmdr. Frey: All right. Jason Sherman with Inside Defense.

Q: Great, thanks. I just want to follow up on the point you made, Dr.

Lewis, there. So you're talking about with the -- with this university

consortium, that's the idea that you're taking and doing better here?

DR. LEWIS: Well, yeah. Okay, so, we've worked with universities.

Obviously, we've worked with universities for decades and decades. So,

but, we looked at, in particular, hypersonics, the degree to which China

will integrate their students working on their various projects. We

thought, huh, that's a pretty good idea. So, yeah.

Q: Great. Thanks. So, Gillian, I wanted to ask if you could just sort

of give us an update, this announcement in the context of other things

your office has done since it was set up in April and in general terms,

sort of explain how Congress gave you $100 million for fiscal year '20,

and it looks like this contract, this 20-year contract, is over five

years, so that's -- that accounts for a small portion of that. So if you

could sort of just walk us through what your main lines of efforts are

in executing those funds that Congress appropriated for fiscal year '20,

and then after that, a question about getting these graduate students

and professors involved in, and integrating them in with these programs

that are classified, what are the implications for foreign students who

might be interested and even involved in some of the disciplines at

these universities? Thanks.

DR. BUSSEY: All right, so I'll address your second question first.

Q: Okay.

DR. BUSSEY: So part of this effort is to train the workforce that

would go into our industrial base, that would work on our programs. So

we are limiting our projects to U.S. citizens and those from -- citizens

of -- and universities from Australia, Great Britain, Canada. We

actually -- I think we have three international universities that we're

bringing into the effort. That's a little challenging how we do that,

but Texas A&M has experience doing that. We also -- part of the

reason why we chose Texas A&M is because they really understood the

security aspect and are actually really proactive in making sure that

those who shouldn't have access to defense university work don't get

that access. They are proactive in looking for counterintelligence

threats, to essentially make sure that we're not training Chinese

scientists who are going to go help their programs, for example. So

that's very much on the top of our minds and we're certainly looking for

ways to ensure that these efforts stay out of the hands of folks who

are going to use it against us in a future conflict. Let's see, remind

me of your first question.

Q: It had to do with $100 million and you guys have been six months

-- you've had six months to spend it and what are the other efforts that

are accounting for those resources?

DR. BUSSEY: Yeah, sure. So our primary lines of effort, the first is

advanced concept development. So we have a contract with Boeing to

mature a dual nose scramjet design. They're working with Air Jet. Air

(inaudible) is our program manager on this effort, and we're doing this

so that we can have a option for the Navy that is compatible with their

F-18 based on -- that are based off of a carrier. We hope to have that

testing wrapped up in time to support any decisions that either the Air

Force or the Navy will end up making in terms of future hypersonic

cruise missile capabilities. Our second effort, what we're talking about

today, the university consortium. Right before -- about two months ago,

we announced eight grants that we handed out to eight different

universities. Those were in the technology areas that I mentioned, as

well as a workforce development grant to look at developing curriculum

for folks in the workforce so that they can get smarter in hypersonics.

So we had a press release about that Monday after September 11th. And

that was just to kind of show that we're still committed to this effort.

But as many people know, we have contracting. Takes a long time. So we

wanted to get something out the door quickly. The third major effort is

our S&T roadmap and strategy. So we have a roadmap that connects

technology need to products, to capabilities, to timelines on when we

need to have those products available to go into programs. And then

also, we appreciate that Congress recognized that it doesn't do much

good to determine what your gaps and your needs are and come up with a

roadmap and then not actually be able to do anything about those gaps

and needs because you don't have funding. So about half of our budget is

going towards 27 S&T acceleration projects. Those are one or

perhaps up to three-year projects that are going to accelerate some our

biggest S&T needs. And so they're spread kind of across the

disciplines. That money's going pretty evenly to the Air Force, DARPA,

Army, Navy, and there's some going to NASA. There's money going to

FFRDC. There's money going to ATL. It's spread pretty -- money going to

(inaudible). It's spread pretty easily across the community. And then

our -- our fourth major line of effort is the system engineering field

activities at NSWC Crane. That was announced last week. And that is

about ensuring that what we're doing has systems engineering rigor

behind it and that the projects for funding, including with the

consortium, they have a pathway and a plan to transition, and a schedule

to transition into block upgrades, to get on flight tests so that can

get matured, and then be in those block upgrades. And then also, we're

responsible for allied engagement in hypersonics. So we have a number of

efforts there with other countries.

Q: And those 27 acceleration projects are separate from the more than

2,000 contracts you plan to award to -- okay, great. All right.

DR. BUSSEY: Yep.

Q: All right. Fantastic. Thank you.

DR. LEWIS: As you can tell, it has been a very, very busy six months

for the JHTO. And shout out to our colleagues in session in the services

and Navy and NSWC Crane, as Gillian mentioned, has just done a

wonderful job with stepping up and working with us as we develop this

portfolio. So we're really proud of the work at JHTO. They've done a

phenomenal job in a very short period of time.

Cmdr. Frey: All right. And then going back to Vago Muradian, did you have a question?

Q: Yes, I -- I did. Thanks very much. So just two -- two questions

really. The -- the first is what's the quantifiable acceleration by

doing this? And if you look at it, while hypersonics may be somewhat

more interdisciplinary than other fields, there are a lot of other

fields that you could apply such an interdisciplinary approach to,

right? So does this make you 50 percent faster? Does this allow you to

have those hypersonics at scale and mass that you're looking for in two

years instead of 12 or one year instead of three? Like, what -- how --

how do we need to think about this in terms of its accelerated

capacities?

DR. LEWIS: So Vago, I got to be honest, I don't know how to quantify

-- I don't know how to give you a quantifiable measure for the question

you're asking. What I can tell you is we want to go as quickly as we

possibly can. So in all of our modernization priorities, we have as a

target date, we kind of think in terms of 2028, the delivery of new

capabilities. Well, why 2028? Because it's ten years after the release

of the National Defense Strategy. It's a line in the sand, if you will.

So across the hypersonics portfolio, we're looking to deliver real

capabilities in just a handful of years. We don't say exactly when

because we've got peer competitors who are carefully monitoring what

we're doing. We do believe that we are in a bit of a race right now. But

-- so the best I can tell you is I -- this is an important part of the

-- when we say acceleration, we mean, basically, every -- we had

previously a number of prototype efforts. Now we're looking to those

prototypes efforts, especially the ones that are most successful, going

-- transitioning directly to programs of record. And so, accelerating

the acquisition process to get us out of the lab and literally in the

hands of the warfighter as quickly as possible. You know, it's just one

example. I'll point to the program in the U.S. Army under -- under

Lieutenant General Neil Thurgood. They are moving at a very, very

aggressive pace to develop the Army component to our hypersonic

portfolio. But, yeah, it's hard to -- I can't tell you that we're

actually 43 percent faster than we were. I don't know how to do that

metric. I can tell you, though, that the whole theme of this is moving

as quickly as we possibly can.

Q: Let me -- let me ask one other follow-up question, if I may. Do

you guys have to do anything differently in terms of security, right?

You were looking for a distributed approach to something that's very

highly classified. Obviously, we do that in a lot of other ways. But is

there anything special that you're doing to maintain security, given the

distributed nature of what you're doing?

DR. LEWIS: I think you mean specifically for the university

consortium. So, Gillian, do you want to talk a little bit about the

security issues? You mentioned them briefly, but --

DR. BUSSEY: So, we literally signed the contract today. So we don't

have the security mechanism set in place. But of the teams we looked at,

this was one of the best and arguably the best in terms of security. So

I can't really say right now if we're doing anything different because

we haven't started doing it yet.

DR. LEWIS: Vago, let me point out, you know, the first step in

security is acknowledging a problem and being sensitive to it. And we

were essentially impressed by the Texas A&M team, that they're -- it

kind of gets back to a question that I was asked earlier. There are

other universities, obviously, that do work in national and

international security. Other universities, other teams at universities

that will do ITAR, will do some levels of classifications. But I think

it was the recognition of the importance in this area, the -- frankly,

the seriousness of the -- of the competition that we face, that we

recognized in this team that -- that was particularly noteworthy. Again,

we had other proposals from other groups that also, and I'm not taking

away from any -- any other proposers. But certainly one -- one of the

winning attributes was starting with the recognition that maybe there's

some special considerations in this case.

Q: Great. Thanks very much, guys. Really appreciate it and congratulations on the agreement.

DR. LEWIS: Thank you.

Cmdr. Frey: All right. With that, we have time for one more question

from someone I didn't call on. And if not, we'll go into closing

statements.

Q: May I ask a very, very quick question.

Cmdr. Frey: Sure. Can you please identify yourself?

Q: Yes, Peter Loewi with the Asahi Shimbun.

Cmdr. Frey: Okay, go ahead, Peter.

Q: Dr. Bussey, you mentioned a sixth -- a formal list of priorities,

but you rambled them off too quickly for me to get them all down. Can

you repeat those six in order please?

DR. BUSSEY: Sure. Materials and manufacturing.

Q: Yep.

DR. BUSSEY: Guidance, navigation, and control; propulsion with an

emphasis on air-breathing propulsion; environments and phenomenologies;

applied aerodynamics and systems engineering; and lethality and

energetics.

Q: Wonderful. Got those. Thanks so much.

DR. BUSSEY: Yep.

Cmdr. Frey: Thank you. All right, Dr. Lewis and Dr. Bussey, we'll go into your closing remarks if you have any.

DR. LEWIS: Sure, well, I just want to thank everyone for joining us.

Obviously, we're incredibly excited about this announcement. One of the

main reasons I came back to the Pentagon was to help enable our national

efforts in hypersonics. And this is such an important step. I want to

thank the whole team, the team led by, on the government side, led by

Gillian, our partners in the services and the agencies that helped us do

the selection. And most importantly the university members who

responded to the call, who worked so hard to put this consortium

together and has -- and have been so open as we've moved forward, as we

developed this effort, and we -- again, this -- we truly are looking at

this as a government/university partnership. This will not be a

situation where we just send funding over the transom and then call up a

year later and say, how's it going? This is going to be a -- a

hand-in-glove partnership between our government folks and industry

partners and our university colleagues. And we are just so excited about

this. And I will give Dr. Bussey the last word.

DR. BUSSEY: Yeah, thank you. So as he just said, we've gained a

partner today, another member of the JHTO team. They're going to be

helping us formulate our S&T strategy. We're gonna be sharing with

them what the Department needs. I remember earlier there was a

discussion about security clearances and classification issues. The

government's for it. There are going to be individuals who we can talk

to frankly about what our needs are. And so I think that this

partnership is gonna make DOD research stronger. It's gonna make it more

-- more in tune with the latest and the greatest that's going out in

the academic community. And at the same time, it's going to make what

the university community is doing more relevant to what DOD needs and

it's going to ease the transition of both technology and workforce into

our programs. Industry is very excited about this. For the last couple

of months, I keep getting questions from our --

Q: (Inaudible) two minor (inaudible) questions to do on this call (inaudible), does that work?

DR. BUSSEY: -- about how they can be involved and when the consortium's going to come online.

Q: (Inaudible). I don't think I need anything --

DR. BUSSEY: Somebody's -- your phone --

Q: There are a couple of things we could use, but nothing (inaudible), see what I mean?

DR. BUSSEY: Okay.

Cmdr. Frey: Please put your -- your phone on mute if you're not speaking.

Q: Well, I mean, I have the codes. I can get it. But let's talk about it another time. I know.

DR. LEWIS: All right.

DR. BUSSEY: Okay. Did you also hear what I -- what I was saying?

DR. LEWIS: Yeah. Hey, once again, everyone, thanks for your time.