What started as a school project has developed into a promising innovation for explosive ordnance disposal operations across the Defense Department.

While completing his degree in electronics engineering technology at

the University of Arkansas Grantham, former Air Force Master Sgt. Daniel

Trombone was challenged to solve a real-world problem within just two

months. Despite limited time and resources, he turned the assignment

into a functional prototype, marking the beginning of the EOD robot

depth-perception system.

"I was doing my senior year capstone and decided to survey my unit,"

Trombone recalled. "I said, 'Hey, are there any capability gaps you

think can be fixed within this short timeline I have?' I ended up

getting a lot of good ideas."

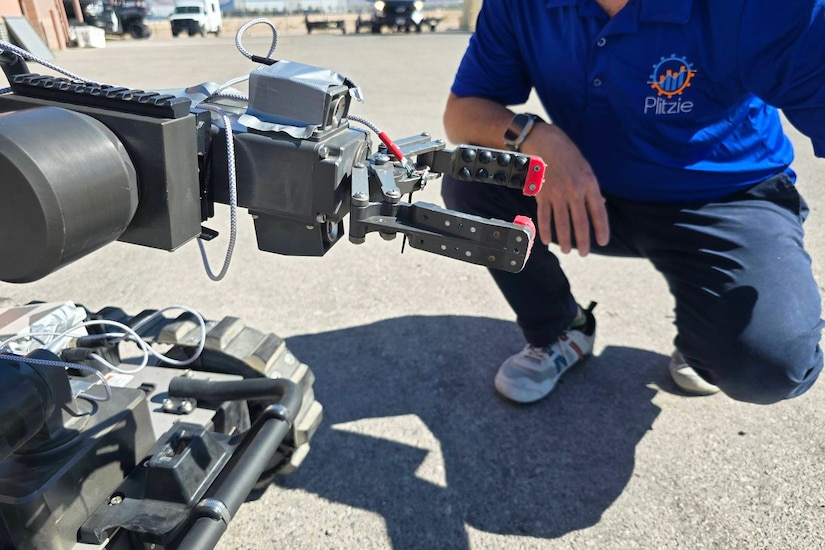

The feedback from his team highlighted a familiar challenge: difficulty

gauging depth when operating EOD robots using a flat, two-dimensional

video feed. Without stereoscopic vision, technicians rely on limited

visual cues and often develop improvised methods, like watching shadows

or attaching zip ties to grippers, to estimate distance.

Trombone set out to design a solution that would place a fixed visual reference in the camera view, giving operators a clearer sense of proximity without the need for extra sensors or complex processing.

The first prototype of the EOD robot depth-perception system was built with hobby-grade components and personal funds.

"I spent my nights in the garage, working at my bench, just trying to

get the thing put together," Trombone said. "Eventually, I got it

functioning."

Once operational, he mounted it to a robot using improvised materials

like C-clamps and tape, aligning the components carefully with the

camera's field of view. Despite its imperfect appearance, the system

succeeded at helping operators better judge distance and handle tasks

with greater precision. As development progressed, Trombone partnered

with Air Force Tech. Sgt. Matt Ruben to further refine the design.

"He's been my counterpart on this project the whole time," Trombone

said. "He's great at CAD design, 3D printing and building things out,

and he helped create the housing and all the brackets that supported the

initial prototype."

After submitting the project and earning high marks, Trombone and Ruben

saw potential beyond the academic setting. But the prototype, though

effective, lacked scalability.

"We knew we were onto something interesting," Trombone said, "but we didn't have a precise product. ... We still needed help from an engineering team."

Seeking a path forward, they discovered the AFWERX Refinery, an Air

Force innovation accelerator, and applied. AFWERX Refinery provides

airmen and guardian innovators with entrepreneurial knowledge,

connections to relevant stakeholders and resources within the Defense

Department.

Through the program, Trombone and Ruben gained critical support,

including development time, funding for travel and research, and access

to key experts. One of the most valuable partners was the Wright

Brothers Institute, which helped guide the next phase by coordinating

industry outreach, identifying capability gaps and securing a

manufacturing partner. That search ultimately led to a defense-trusted

engineering and analytics firm to lead manufacturing prep with Trombone

and Ruben and deploy the advanced robotics sensor.

Also recognizing the value of the concept, the Air Force Lifecycle

Management Center pursued intellectual property protection, filing a

patent application in June 2023.

"If it's approved, that's a bonus, but our goal has always been mission impact," Trombone said.

Designed to be low cost and easy to implement, the system is poised

to be adopted across EOD units in the Air Force and joint partners. The

team aims to keep the unit price low enough for teams to procure the

system within existing budgets.

"If this reduces the need for technicians to approach [improvised

explosive devices] in person and allows for faster, safer robotic

operations, then we've achieved our mission," Trombone said.

Reflecting on the project's evolution, he emphasized the importance of collaboration and institutional support.

"We wouldn't be where we are today without a strong group of

stakeholders," Trombone said. "Dozens of people have contributed, some

throughout, others at key moments, but it's definitely not a one- or

two-person show. It takes a whole team to get something like this off

the ground."

To other airmen pursuing innovation, he stressed the value of patience, adaptability and a willingness to learn. Turning a good idea into an operational solution often means managing both the technical development and the process behind it. Understanding how to navigate project timelines, stakeholder engagement and the realities of scaling a concept can be just as important as the idea itself.

No comments:

Post a Comment