By Matthew Schehl Naval Postgraduate School

MONTEREY, Calif., April 6, 2018 — Two students at the Naval

Postgraduate School here have created a way to bridge a training gap in U.S.

military cyber operations -- through a game.

"The goal of CyberWar: 2025 is to stimulate and

increase players' knowledge and experience of cyberspace operations,"

Mulch said. "The basic idea is to learn as you play."

In approximately 30-60 minutes of turn-based, 'sandbox'

gameplay, players employ a range of the basic concepts laid out in Joint

Publications 3-12(R) Cyberspace Operations. A deft combination of offensive

cyber operations, defensive cyber operations and computer network exploitation

can lead a player to victory, even if in a relatively weak position.

"Everybody starts out on a level playing field,"

Mulch explained. "Players utilize resources in a way they see fit, whether

those resources are put into offense, defense or reconnaissance."

Critical Time

Long and Mulch developed CyberWar: 2025 at a critical time.

A sense of urgency has burgeoned in the United States over

the last decade as adversaries – state and non-state actors alike – have

increasingly turned to the cyber domain to actively work against U.S. national

security interests.

In a recent speech at John Hopkins University, Defense

Secretary James N. Mattis reiterated that the Defense Department absolutely

must "invest in cyber defense, resilience, and the continued integration

of cyber capabilities into the full spectrum of military operations."

"Our competitive edge has eroded in every domain of

warfare – air, land, sea, space, and cyberspace," he said. "And it is

continually eroding."

President Donald J. Trump echoed this in his fiscal year

2019 budget request to Congress, calling for a 4.2 percent increase in the

Pentagon's cyber funding to $8.5 billion as U.S. Cyber Command approaches full

operational capability as a newly-unified combatant command.

"What's going on in cyber policy is a big question

right now in DoD," Mulch said. "What does our competitive balance

look like? Should we be strong? Should we be putting time and resources into

defense, reconnaissance or research?"

And yet, there remains a critical gap in how DoD goes about

preparing the military to engage in this domain. Several educational courses

and training exercises have been developed to prepare leaders to plan and

execute cyberspace-based effects to support operations, but there are no

virtual simulations used by the military to train and educate service members

in the basic concepts of cyberspace operations.

Filling a Gap

When Long, a cyberwarfare practitioner at Fort Meade,

Maryland, and Mulch, an information operations officer, arrived at the Naval

Postgraduate School in June 2016 to begin their graduate work in information

strategy and political warfare, it didn't take them long to turn to solving

this.

"People would say I'm the cyber guy, even though I

really don't like that term," Long said. "When I came to NPS, my

promise to myself was to [impact] the Army cyber mission; I had a lot of ideas

about how we can educate people about cyber operations, and how we could do it

correctly."

Attending a game theory course, they encountered an article

exploring the strengths and weaknesses of American cyber capabilities vis-a-vis

Russia and China. Over spirited arguments over how much emphasis the U.S.

should be placing on offense, defense or reconnaissance, the kernel of CyberWar:

2025 was formed.

"We used game theory to explore that, but that was the

basis of 'hey, I think we have a question here that we could look into,'"

Mulch said.

Army War-Gaming

Coming up with a game was not too far a stretch: the U.S.

military has a long history of using games to prepare, understand and even plan

for war. The earliest use of war gaming in the U.S. dates back to 1883, when

Maj. William R. Livermore used topographical maps to practice the art of war.

Livermore's work was itself based on Kriegsspiel, a tabletop game the Prussian

military had used since 1812 to train its officers.

However, such gaming is not just "beer and

pretzels," Long stressed. Serious games, which academic literature refers

to as "gamification," are played to stimulate creative thinking,

decision making and problem solving to learn. Good gamification allows players

to synthesize new knowledge and make critical judgements.

"With CyberWar: 2025, what we're really looking at,

other than reinforcing terminology, is letting people learn through discovery

what the relationship between cyber effects is," Mulch said.

For example, if a player has developed strong defensive

capabilities but weak offensive capabilities, what would a potential conflict

look like with an adversary with strong offensive capabilities?

"In a nutshell, that's what CyberWar: 2025 provides: An

interactive experience for you to reinforce concepts and potentially look at

other ways to solve a problem," Mulch said.

Game Play

The game, he said, is intended to feel like Diplomacy, a

classic 1954 strategy board game that relies as much on player interaction as

moving pieces around a board.

At the beginning of CyberWar: 2025, six players are

randomized for anonymity, so you could be sitting next to somebody, but not

necessarily be located next to them on the board.

Play then proceeds simultaneously by round, with each player

submitting their orders, which are resolved all at once before the next round.

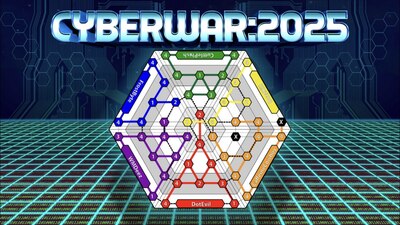

"The players communicate with each other and maneuver

around the map, which consists of 48 interconnected 'server nodes' that are

represented by hexagons," Mulch explained.

As players capture new server nodes, they gain points which

they then use to either conduct an action or research three tiers of new, more

advanced effects for these actions.

"The more points you have, the more you can put into

effects, and then you can use these to launch attacks against your adversaries

and so forth," Mulch said.

The game play is simple and intuitive, but there's a lot

going on under the hood.

When all players have submitted their orders, the software

engine running the game sorts their input, calculates each of their actions,

analyzes the results and then broadcasts these back to the players within a

split second.

Training Applications

"What we accomplished over a tight nine-month time

frame was to effectively pack ten pounds of product into a five-pound product

bag," Long said. "You learn by making mistakes: you can explore

multiple paths and if you make a mistake, that doesn't mean you lose the

game."

From inception, Long and Mulch designed the game to be

applicable for all branches of DoD and their subordinate cyber fields, as well

as an educational tool for decision makers and leaders on cyber policy.

Since their thesis was published in December, CyberWar: 2025

has been successfully adopted in cyber courses at NPS, though Long and Mulch

would like to see it become more widely available.

"The way forward is to have it incorporated into cyber

education courses across the services," Mulch said.

It also has great potential as refresher training, the duo

said. For service members who've already received cyber training, yet haven't

practiced it for some time, CyberWar: 2025 serves as an efficient tool to get

them back up to speed prior to deployment or a training event.

"Whether they're about to go out to the National

Training Center at Fort Irwin, California, the Joint Readiness Training Center

at Fort Polk, Louisiana, or anywhere else, CyberWar: 2025 could be implemented

as a reinforcement tool at the home station pre train-up before they go into an

actual exercise," Long said.

CyberWar: 2025 has been effectively used in the classroom at

NPS, but the students hope to soon see the application available to a broader

DoD audience. With further development, incorporating computer-controlled

players, Long and Mulch see the opportunity for a DoD-wide training tool.

No comments:

Post a Comment